Are we any clearer on what it will look like?

It's been nearly two years since the UK government consulted on a possible regulated asset base (RAB) model to support future nuclear power plant projects. We reported on this in our Insight, Net Zero needs the nuclear option. Now we have the Nuclear Energy (Financing) Bill going through Parliament, but is it any clearer how the model will work?

- Why Nuclear?

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has led to commitments from the West to reduce reliance on Russia for gas and oil. Whilst the UK itself is not as reliant on Russian oil and gas as other countries, we are feeling the impact of increased prices. Energy security is once more at the forefront of Government thinking. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said this week that "now is the time to make a series of big new bets on nuclear power" and we are expecting a UK Energy Security Strategy later this month, which we expect will advocate the expansion of nuclear power.

The government sees nuclear power as essential to meet the legally-binding net zero target set by the Climate Change Act 2008. Yet almost all our current operational nuclear power stations are due to come offline by 2030 as they reach the end of their operational lives. New nuclear power stations are expensive and risky to finance, with much of the money needed up-front, long before they can start to generate revenue by selling power. The only nuclear power station currently being built in the UK, Hinkley Point C, has been supported by the Government via a Contract for Difference (CfD), but this only guarantees a certain level of revenue once the plant has begun generating electricity; the investors still have the construction and operating risk.

There are large volumes of private sector capital (mainly pension funds and insurers) who are looking to invest in infrastructure projects, but only if their exposure to risks are within limits. This is why the government is proposing a RAB model. The fact that investors have pulled out of the Wylfa Newydd and Moorside nuclear projects since the consultation on a RAB model for nuclear was first launched shows why this is needed.

- Developments since the July 2019 consultation

The government published the Consultation response in December 2020 and has now introduced the Nuclear Energy (Financing) Bill to Parliament. The Bill has passed the House of Commons stages and is now being considered in the House of Lords.

The Energy White Paper, also published in December 2020, committed to bringing at least one new large-scale nuclear project to final investment decision during this Parliament, subject to all relevant approvals. It looks like this is likely to be Sizewell C as in January 2022 the government announced £100 million of funding in the form of an option fee that will be invested by EDF into the project to help bring it to maturity, attract investors, and advance to the next phase in negotiations. EDF will reimburse this as either cash or shares in the project if it reaches a final investment decision and if not, will refund it.

- The RAB Model

The Energy Minister Greg Hands, introducing the Nuclear Energy (Financing) Bill to Parliament, said “This new funding model will reduce our reliance on overseas developers for financing new nuclear projects. It will substantially increase the pool of potential private investors to include British pension funds, insurers and other institutional investors.” But what does it involve?

Structure

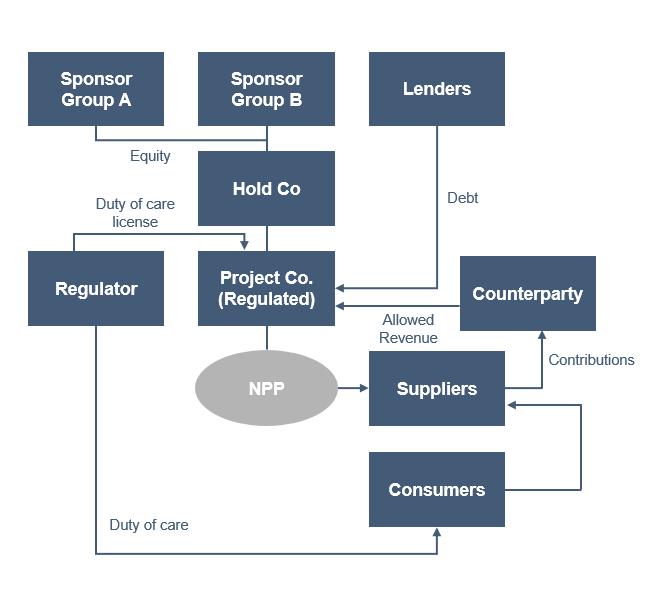

The RAB model is a type of economic regulation typically used for monopoly infrastructure assets such as water, gas and electricity networks. A company receives a licence from an economic regulator, granting it the right to charge a regulated price to users (which would be electricity suppliers) in exchange for the provision of the infrastructure in question. Suppliers would pass on the charge to consumers via their electricity bills. This chart explains the basic structure:

Allowed Revenue

The charge (Allowed Revenue) is set by an independent regulator (in this case, Ofgem) and can be adjusted throughout the lifecycle of the licence to ensure that the company's costs are recovered and a permitted profit margin is maintained. Ofgem holds the company to account to ensure that any expenditure is in the interests of customers.

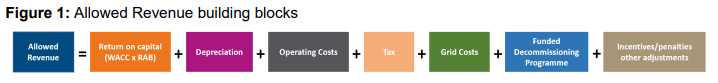

According to this diagram taken from page 13 of the RAB consultation, the Allowed Revenue is made up of:

The ‘Weighted Average Cost of Capital’ (WACC) would be the cost of capital allowed by the Regulator.

The ‘RAB’ (also referred to as the Regulatory Capital Value or RCV) would be the total cumulative capital expenditure as incurred and approved as being efficient by the Regulator, as adjusted for indexation and Depreciation.

‘Depreciation’ would allow repayment of the initial capital cost of the RAB value during its operational life so that, by the end of operations or earlier, all capital invested in the plant and approved as efficient by the Regulator would be paid back to investors.

‘Funded Decommissioning Programme’ (FDP) would make provision for the decommissioning and waste management costs associated with a new nuclear project. It is envisaged that this would apply from the point of nuclear operation for the remainder of the period in which a regulated Allowed Revenue was charged, with incentives placed on costs within the project company’s control. (This is an extra item that is not found in other RAB models, but is needed because the cost of decommissioning a nuclear project is very large and needs to be factored in at the outset.)

The Allowed Revenue would be charged during both the construction and operational period, with charges increasing over the construction period in line with the cumulative project spend. A potential challenge with this approach is that it would expose suppliers and their consumers to the risk that they provide construction-phase funding for a plant that is never completed. To deal with construction cost risk, the Government has recommended using an 'ex ante' cost settlement model, in which the target total construction cost for the project would be set at the point at which the RAB licence was granted, with the project company and suppliers (and in turn, customers) sharing the risk of additional costs and the benefits of any costs savings.

Revenue Stream

The Allowed Revenue would effectively be funded by electricity suppliers, who would then recover the cost from their customers. An intermediary body will collect payment from suppliers and pass this on to the project company.

- Nuclear Energy (Financing) Bill

The Nuclear Energy (Financing) Bill was introduced to Parliament on 26 October 2021 (see press release.) It has passed through the House of Commons with minimal amendments and is currently in the House of Lords. However, the purpose of this Bill is simply establish the framework for the deployment of RAB in the civil nuclear sector. The detail of each RAB model will be considered for each specific nuclear project and implemented through secondary legislation in due course.

The Nuclear Energy (Financing) Bill has four parts.

Designating a company as eligible to receive RAB funding

Part 1 covers the procedure by which a secretary of state would be able to designate a nuclear generation company as eligible to receive funding through a RAB. To do this, the Secretary of State must be of the opinion that:

(a) the development of the nuclear project is sufficiently advanced to justify the designation, and

(b) designating the nuclear company in relation to the project is likely to result in value for money.

Once they are ‘designated’ the Secretary of State will be able to amend their existing generation licence to insert the special conditions of a RAB that set out how the project will be regulated and its allowed revenue calculated.

The Final Investment Decision (FID) for a specific project would be made after it has been designated and before any final licence amendments. The revenue collection contract will be made after this.

Revenue collection counterparty

Part 2 sets out how contracts between the nuclear company and the body responsible for collecting payments from electricity suppliers (the ‘revenue collection counterparty’) would work. The revenue collection contracts will be used to fund a nuclear company. The revenue collection counterparty will enter into and manage revenue collection contracts with the nuclear company and will act as the interface between them and suppliers. Suppliers are expected to pass the cost on to consumers. Costs will start to be charged to consumers during construction, based on the allowed revenue due for the period. During operation the cost will be the allowed revenue due, minus the value of selling the energy generated.

Special administration regime

Part 3 of the Act sets out a ‘special administration regime’ which would apply should a nuclear company become insolvent. This is modelled on that set out in the Energy Act 2004 (which was used for the first time in November 2021 when Bulb became insolvent). If a generator with a RAB contract becomes insolvent (which the Government considers very unlikely), the Government can apply for a court order to appoint a special administrator to manage that generator and the plant. They would have the objectives of maintaining (or restarting) energy generation and rescuing the generator.

Insolvency under the RAB model poses an additional risk to consumers. This is because it entails consumers paying (through their energy bills) during the construction phase of the plant, before it has generated any electricity. So there is a risk that a generation company could become insolvent during the construction phase with the project unfinished, potentially resulting in consumer loss.

Funded decommissioning programmes

Part 4 of the Act concerns the definition of which bodies are ‘associated’ with a nuclear project for the purposes of funded decommissioning programmes. This aims to clarify that secured creditors and security trustees are not considered 'associated' with the nuclear company so are not liable for funding a decommissioning programme. The intention is that this will remove barriers to private financing of nuclear projects.

What we still don't know

The Bill sets out the skeleton of how the RAB model for nuclear will work, but the details are left to regulations. The key thing will be designating a company as eligible to receive funding through a RAB model. Clause 3 of the Bill requires the Secretary of State to publish a statement setting out the procedure for considering whether to designate a nuclear company and how they will judge it against the criteria set out in clause 2 (that the Secretary of State is of the opinion that the development of the nuclear project is sufficiently advanced to justify the designation; and that the Secretary of State is of the opinion that designating the company is likely to result in value for money). The statement can be published before or after the Bill is passed. So until it is published, we don't know exactly what will be taken into account, but the explanatory notes to the Bill suggest the Secretary of State will have regard to matters such as ensuring the security of supply; the cost to consumers; ensuring the provision of low carbon electricity; and achieving UK 2050 net zero obligations.

Next steps

According to the impact assessment, the Government expects to ‘designate’ a project at Royal Assent of the Bill and then move to modify the licence conditions in quarter four of 2022.

Comment

The Government believes that the RAB model will reduce the overall cost to consumers of new nuclear power. This is because the payments available during construction, before the plant starts selling power, means project owners will be able to settle financing costs sooner in the life of the project, thereby reducing the overall cost of capital. By transferring some of the construction risk to the consumer it is also hoped that developers price-in less in the way of risk premiums when compared the CfD model. The Government estimates that using a RAB rather than a contracts for difference model, as has been agreed for Hinkley Point C, will save consumers between £30bn and £80bn (see the Impact Assessment). However, in an era of soaring energy prices, including for wholesale electricity, prior estimates may need to be revisited.

The Government also believe that the RAB model improves the chances of gigawatt scale nuclear plants achieving financial close – and actually being built – by attracting a broader pool of development capital. The withdrawal of Hitachi and Toshiba from the UK new build market – and with them the effective cancellation of the Oldbury, Wylfa and Moorside projects – demonstrated that the CfD model left the UK too reliant on a handful of industrial developers whose ability to successfully finance projects are subject to the limitations of their own balance sheets. The key developers also all happen to be non UK entities. With the RAB designed to alleviate some of the key risks that made nuclear under CfD un-investable for most, the Government hopes that the future projects can be developed with a more diversified and dynamic capital stack – including pure financial investors (such as pension funds) as well as perhaps some limited recourse debt.

Richard Goodfellow

Head of IPE and Head of Energy and Utilities (Global)

United Kingdom