In October last year, the UK Energy Minister Kwasi Kwarteng committed the UK to fully decarbonise the electricity system by 2035, subject to security of supply.

The British Energy Security Strategy of April 2022 promised a review of the British electricity market arrangements to see if they were still fit for purpose. Now, just in time for the summer holidays, here it is.

It is a wide-ranging review that affects anyone participating in British electricity markets, whether that be the wholesale market, the balancing mechanism, ancillary services, the Contract for Difference (CfD) or the capacity market. It will also affect the Dispatchable Power Agreement for power CCUS, the Regulated Asset Base model for large-scale nuclear, and the interconnector cap and floor. All of these could change. This means you will need to look again at your business models.

Vision for future market arrangements

The Government wants future market arrangements to:

- Deliver a step change in the rate of deployment of low carbon technologies, and reduce our dependence on fossil fuelled generation

- Provide the right signals for flexibility across the system

- Facilitate consumers to take greater control of their electricity use by rewarding them through improved price signals, whilst ensuring fair outcomes

- Optimise assets operating at local, regional, and national levels

- Ensure that the security of the system can be maintained at all times.

Current market arrangements

Chapter 2 of the Review looks at how the electricity market currently works and concludes that the market alone in its current form can't deliver the vision. The existing market is based on bilateral trading between generators, suppliers, customers and traders. There is national pricing, technology neutrality (all technologies are treated the same) and participants choose when to generate power ('self-dispatch') rather than the Electricity System Operator doing it centrally.

The price is based on short-run marginal cost: each generator bids their price to produce the next unit of electricity and the price is set at the level which ensures all demand is met. Renewables will bid a low price as it does not cost anything to produce electricity (wind and sun are free). Gas generators on the other hand have their fuel costs. If renewables cannot supply all the power needed, gas generators end up setting the prices, as they are brought in to make up the shortfall in supply. The steep rise in gas prices over the last few months has therefore had a knock-on effect on electricity prices, even though much of GB's electricity comes from renewables.

A market based on short-run marginal pricing doesn't help renewables. They need their long-run marginal costs covered: they cost a lot to build but once running, have low operating costs. When lots of renewables are generating together, they can meet demand so this drives the wholesale market price down towards their own short-run marginal costs, which are close to zero. This is known as 'price cannibalisation'.

- Options for reform

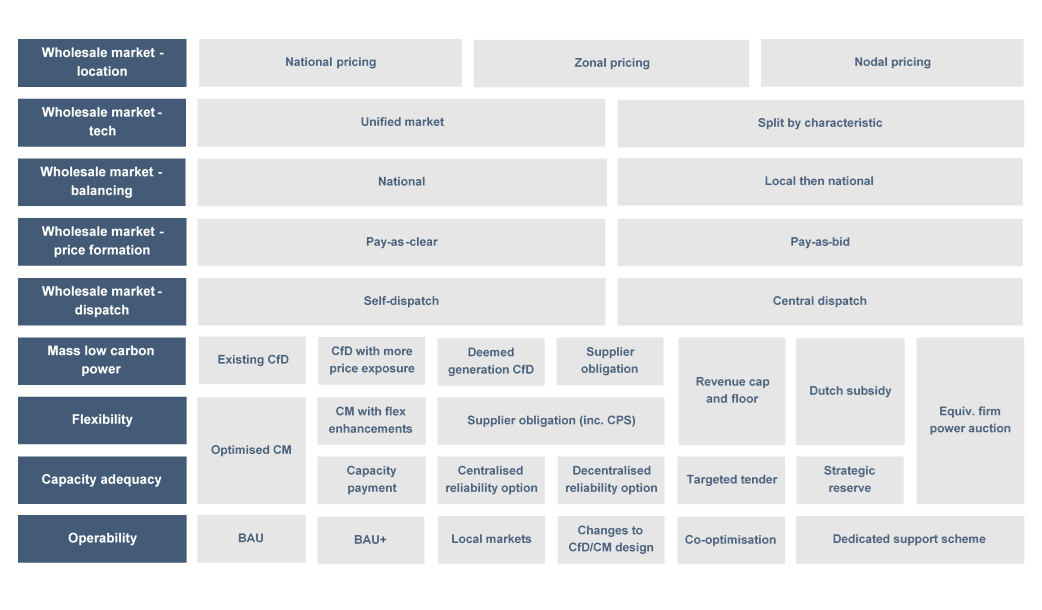

At this stage of the Review, there are various options on the table (see chart). The Government will narrow them down before starting to package them up together. Packages will include at least one option from each row. Not all are compatible with each other. Some would mean a lot of changes to the market and would take years to implement, others are more incremental reforms to current arrangements.

© BEIS, July 2022. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/

The government will consider options for reform against five key criteria:

- Least cost - Market design should lead to solutions being developed at least cost to consumers.

- Deliverability - Market design changes should be achievable within designated timeframes.

- Investor confidence - Market design must drive significant investment in low carbon technologies.

- Whole-system flexibility - Market design should incentivise market participants of all sizes (both supply and demand side) to act flexibly where it is efficient to do so.

- Adaptability - Market design should be adaptive and responsive to change.

Without going into detail on every possible option, some of the key ones include:

Locational pricing – having different prices for electricity depending on where it is generated. This could be either nodal pricing (based on transmission nodes: there are hundreds across GB) (also known as locational marginal pricing, 'LMP') or zonal (regional areas). Ofgem the energy regulator and NGESO the electricity system operator have both been recommending some form of locational pricing. Other countries do this (e.g. the USA has nodal pricing; Europe is split into zones).

The benefits of locational pricing are that it will help to resolve network congestion and will mean the system operates more efficiently: energy will be generated where it is needed.

The major downside is that renewables can't always decide where to locate. They have to be where it is most windy/sunny which may not be where the demand is. This could lead to increased investment costs for comparatively little benefit. It may also mean consumers in some areas pay higher power prices than others.

Splitting the market into separate markets for variable and firm power. Variable power means power that is not constant but depends on how much the wind blows or the sun shines (also known as 'intermittent' power). Firm power is power that can be switched on (or off) on demand, so usually means gas fired power stations.

The variable power prices would be set on the basis of the long-run marginal cost of renewables; firm ('on demand') power prices would continue to be set by the short-run marginal cost, as they are now.

The benefits of this are it would reduce price cannibalisation and it also places a value on flexibility: you can buy power at lower prices when lots of renewables are generating. The downside is that it is a theoretical concept that has never been done in other markets and there are still fundamental design questions to be answered.

Changing the CfD – renewable generation with a CfD is paid a fixed strike price for each unit of electricity it generates. This means it is not incentivised to respond to market forces, it just generates as much as it can, to get paid. Some options are to add variants that will increase price exposure, for example a strike range rather than a strike price; or a cap and floor mechanism like for interconnectors, where plants can compete in all the markets (wholesale, capacity, balancing, flexibility services) and are topped up to a minimum revenue if necessary.

The Review does not seem to be suggesting that existing CfDs would be amended. The changes would just apply to future CfD rounds.

Supplier obligations – suppliers could be given an obligation to procure green energy directly on their consumers' behalf. This leaves it to the market to decide how best to meet this, rather than government dictating. But it raises financing and delivery risks: there would need to be intermediaries between generators and suppliers and this could lead to higher financing costs for renewables projects.

Another form of supplier obligation proposed is a Clean Peak Standard requiring suppliers to use low-carbon electricity or reduce demand during times of peak demand. This could help provide stronger investment and operational signals for flexibility assets (i.e. assets that can turn on/off/up/down at short notice to meet peak demand or an oversupply).

Changing the Capacity Market (CM) – one option is an optimised CM for low carbon technologies (similar to what was proposed in the CM Call for Evidence July-Nov 2021). This would involve separate auctions for low carbon assets; or having multiple clearing prices depending on capacity type. Another option is to introduce specific auctions for flexibility (e.g. response time and duration) open to all low carbon technologies which meet an agreed set of flexibility criteria. But this would make the CM more complicated.

A further option is to introduce multipliers to the clearing price, such as: response time – the speed at which assets can respond to signals; duration – the ability to sustain capacity over a prolonged period of time; location – the benefit to the system, depending for example on how near they are to constrained areas.

- Next steps

The REMA consultation closes on 19 October. The Government has said it will respond in "winter" then develop reforms in 2023. There will be a full delivery plan and implementation from the mid-2020s.

Comment

At the moment, every part of the electricity market is eligible for reform. The Government have done a thorough job of assessing the limitations of the current market and the possible ways to solve these.

There are some key decisions to be made: whether to introduce locational pricing (this seems likely given that Ofgem and NGESO are in favour); whether to have central dispatch instead of self-dispatch (this would mean an enhanced role for the Future Systems Operator/Independent Systems Operator and Planner function that is currently being split off from National Grid – a move towards re-nationalisation?); and whether to have separate prices for firm and variable power.

What we do know is that the changes will affect all players in the electricity market and will mean recalculating financial models. In the short term, it is likely to make investors more nervous. When the world is on a deadline to decarbonise, anything that hinders investment in low-carbon power is detrimental. Do respond to the consultation with your views and contact one of us for help and advice.

Richard Goodfellow

Head of IPE and Head of Energy and Utilities (Global)

United Kingdom