The title will only mean anything to the Blue Peter generation, but what are the pros and cons of including examples in contracts, and what are the pitfalls to avoid?

Two cases[1], the most recent of which was decided last month in the Commercial Court, provide some useful pointers. In both cases, the Court decided that the examples were the more reliable indicator of the parties' intentions.

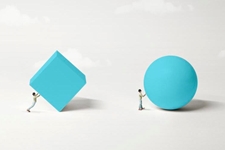

The first question is why include examples in contracts at all? The reasoning would be that if the words or formulae used are clear, then there should be no need for examples. If the words aren't clear enough, then (it would be argued) one should clarify them rather than 'drawing a moustache' on the picture by adding in examples.

Further, it might be argued that the potential for uncertainty and unexpected outcomes is heightened by including examples because it raises the possibility of a clash between the substantive contractual provisions and the examples.

But such criticism overlooks a number of potential benefits from inserting examples, many of which arise outside the sphere in which contracts are considered as part of litigation, including the following:

- during the negotiating process with the other party, examples can be useful in confirming that the parties do indeed share a common view of the way in which the contract is designed to operate; with one's own client there is similarly the possibility to double check that there is a shared understanding. I'm sure I'm not the only practitioner to find that, on occasion, when examples are produced, it is discovered that there is no consensus and that some redrafting is called for;

- the counter-argument might be that examples could be created but remain outside the contract itself; the reality of this approach, however, is likely to be that the examples will then receive scant attention when all parties and their advisers are rushing around trying to agree remaining points and populate the inevitable missing schedules; and if they have no contractual significance, even if reviewed and approved by the parties, that review may in reality have been only superficial. Admittedly, they might form part of the surrounding circumstances to be taken in to account in interpreting the contract, but no more than that;

- in both of the cases we will consider in a moment, the Court decided that the examples were valid and effectively over-ruled the 'main body' of the contract; assuming that that approach resulted in the parties' genuine intentions being given appropriate effect, the absence of examples would presumably have resulted in the 'wrong' outcome, based solely on erroneous or misleading wording or formulae in the main body of the agreement; and

- finally, in longer-term or very complex contracts, worked examples can assist those coming to the contract long after execution to comprehend both how the contract works and what the shared understanding of the original participants in negotiations was, potentially some time after those individuals have left the business.

So if I have convinced you of the attractiveness of including examples in contracts in appropriate circumstances, what can we draw from these cases?

The older case is the Court of Appeal's judgement in Sutton v Rydon. In that case the court was faced with a conundrum: various provisions of the contract depended for their operation on the contract containing "Minimum Acceptable Performance Levels" or "MAPs". The problem was that no MAPs were set out in the body of the contract, The only place they were to be found were in some illustrative examples attached to the contract.

So the Court either had to give effect to the MAPs in the illustrative examples so that elements of the substantive agreed terms would operate as intended, or accept that the examples, and the MAPs contained in them, were not part of the contract and that therefore the parties' presumed intentions in relation to those substantive elements which relied on MAPs would be frustrated.

Applying the reasoning on contract interpretation from Arnold v Britton and other recent cases on contract interpretation, the Court of Appeal overruled the Technology and Construction Court, finding that the MAPs were indeed a binding part of the contract.

The Commercial Court in the recent Altera case faced a slightly different question: what happens when substantive elements of the contract are at odds with each other?

The Court decided that the examples should prevail, saying that:

“It seems to me to be inherently more probable that the parties’ true bargain is to be found in the “Worked Examples”

Worked examples deserved particular attention being something to which the parties had particularly turned their minds, which meant that the examples were the true expression of the parties' shared intention., and here there was not one but two worked examples.

The Court sidestepped the issue of the precedence or inconsistency clause: as it was not clear that anything had gone wrong in the drafting, there was no role for that provision to play.

It is odd that the Court did not refer to Sutton v Rydon, actually stating that the parties had been unable to find any pertinent case law save for the Starbev case from 2014.

Remembering that the conclusions reached by the Courts in these cases are not rules of law, but driven by the familiar rules of contract interpretation on a contract-by-contract basis, what are we to conclude as regards using examples? I'd suggest the following takeaways:

- examples remain a good idea where complex formulae etc are involved; these decisions do not contradict the points made above about the utility of examples;

- however, it's crucial that the worked examples and the substantive text are congruent;

- if they are not congruent, it is very possible that the examples will prevail, as occurred in both of these cases;

- it's probably a good idea to ask a numerate colleague who doesn't know the transaction to double-check the workings; after all, a judge in any court case will be in the same position as them!

[1] Sutton v Rydon (CA) (18.5.17) and Altera v Premier Oil (Commercial Court) (17.7.20)